New York has been home to more distilleries, taverns, speakeasies and dives than anywhere else.

No matter what you think about alcoholic beverages (I’m a teetotaler myself) they’ve been an integral part of city life from the very beginning. Whether an accompaniment to dining, dancing, celebrations or religious ceremonies, or imbibed for its inebriative effects, booze is a central ingredient of New York’s history, industry and culture. From Dutch grog shops, German beer gardens and Bowery dives, to Prohibition speakeasies, “Café Society” nightclubs and groovy discotheques, New York has always grabbed the drinking spotlight.

“Barroom Dancing” by John Lewis Krimmel, 1820. (Library of Congress) Select to enlarge any image. Phone users: finger-zoom or rotate screen.

Let us begin our tippling journey with a history of New York’s drinking establishments. Then we’ll mix some cocktails, saunter through Prohibition, and visit some classic taverns which still delight today’s city folk.

Wild and rowdy New Amsterdam

Upon establishing its tiny trading post on the Hudson in the 1620s, one of the first things the Dutch West India Company built was a distillery on Staten Island, the earliest of its kind in America, which produced many types of spirits. It wasn’t long before the first beer brewery was constructed on Stone Street in lower Manhattan (which remains a cobblestoned draw for bar-hoppers today.) Within its first decade, the fledgling colony was awash in alcohol.

Stone Street today.

The Dutch loved to drink, and brought their thirst with them to the New World. Men, women and children drank beer at meals and throughout the work day. They considered alcoholic beverages more nutritious than plain water, which they regarded as impure and suitable for only the poorest. (In a few decades this would prove to be true for all New Yorkers.)

In the 17th-century, New Amsterdam was alone in this mass manufacturing and consumption of booze. Puritan New Englanders and Pennsylvanian Quakers believed intoxication was sinful. Southern colonists had no big cities to support distilleries or breweries. Only the rough-and-tumble Dutch colony (whose island “Manahatta” may have meant “place of general inebriation”) made unbridled quantities of spirits and established taverns...lots and lots and lots of taverns (often called “groceries,” as in the painting below. Zoom in!)

“The Five Points” by unknown artist, 1827. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Author Caleb Carr points out how the Dutch period set the pattern for behavior in New York: “There was an absurd ratio of citizens to taverns. It was virtually that every 20 guys had their own tavern, and it remains a ratio that’s probably pretty close to the way the city has remained throughout its history.” Other researchers state that one quarter of all New Amsterdam buildings were “grog shops,” selling nothing but beer and tobacco. Drinking and public rowdiness were a huge problem. The first laws established in New Amsterdam were to control drinking, banning it on Sundays and forbidding sales to Native Americans and enslaved people. Despite these efforts, a century later it was estimated that there was a tavern for every 45 men, women and children in the city.

Let’s visit a tavern

Colonial taverns (“public houses” or “ordinaries)” provided much more than drink and food. They were also hotels, municipal buildings and post offices. Business meetings and political gatherings were mainstays. It was in taverns that American patriots or “Liberty Boys” planned the Revolution. Taverns also offered gambling, bowling, billiards, and entertainments such as cockfighting and bearbating. It was a man’s world.

Bull’s Head Tavern, Bowery, 1783.

In a tavern you sat at a table, never at a bar. The word “bar” referred to the store of spirits which was locked inside a barred cage. Only the “bar-tender” held the key.

The most popular Colonial drinks were locally-made beer, ale and cider, as well as imported brandy, rum (a product of the West Indian slave/sugar trade), and fortified wines like port and Madeira. There was also a galaxy of mixed drinks (an American invention) all served warm: flips, possets, grogs, syllabubs, nogs, shrubs, toddies, bounces, sangaree (similar to sangria) and an array of milky punches. New Yorkers preferred to be warmed by their drinks; icy-cold refreshments like cocktails are a more recent invention, thanks to readably-available ice.

“A Midnight Modern Conversation” by William Hogarth, 1733. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

By 1773 there were 393 licensed taverns in New York City, and many more illegal ones. 17 rum distilleries produced 4.6 gallons of rum per person annually. Such excess of booze was required when the city became the nation’s capital in 1789, which engendered endless assemblies, galas and balls.

The man who catered much of this hubbub was a biracial immigrant from the French West Indies named Sam Francis, who changed his name to Samuel Fraunces after the Revolution. He established Fraunces Tavern at 54 Pearl Street in 1762. Despite three fires, it still stands, the oldest building in Manhattan. You can visit its Long Room, where George Washington said farewell to his tearful troops, and also a small museum.

Inside Fraunces Tavern today.

The City Hotel (1794 - 1849), located in today’s financial district, was the first functioning hotel in New York. It boasted the city’s first lobby bar, a hotel tradition which continues to this day throughout the city. It originally featured a liquor cage (as described above) which was eventually fronted by an intricately-carved stand-up “bar” with brass foot rails; the first of its kind. It also boasted the first true bartender (as we know them today), Orasmus Willard. He lived at the hotel, never forgot the face of a customer, and introduced drinks like the Mint Julep and Apple Toddy.

The City Hotel on Broadway, 1831.

Two New Yorks

Ever since its beginning, the city has been home to both the wealthiest and the poorest people in the world, living virtually side-by-side. During the 19th century this financial gap widened exponentially. In 1845 there were 25 New York millionaires. By 1890, there were over 4,000. New York’s Gilded Age had arrived. Meanwhile, in the tenement slums of the Lower East Side, things weren’t so gilded. The immigrant neighborhood swelled to become the most densely populated place on earth, riddled with disease, homelessness and starvation. But no matter how rich or poor, most New Yorkers still needed to drink. The saloons of the time reveal much about both sides of the Big Apple.

Besides dining at ritzy restaurants like Delmonico’s or “lobster palaces,” the wealthy could take liquid refreshment at swanky hotel bars, such as the one at the Metropolitan Hotel on Broadway. It was here that the world’s premier bartender, the bejeweled Jerry Thomas (see bio), served his flamboyant concoctions to a glittering crowd of tuxedoed enthusiasts, while he gathered notes for his magnum opus, The Bar-Tender’s Guide, the first recipe book for drinks. The cocktail was born! (there’s another bio link at the end of this chapter)

At the center of Manhattan, near Madison Square, stood the Hoffmann House. Its barroom featured an enormous fleshy painting, “Nymphs and Satyr,” which newspapers trumpeted into a national sensation. The hoi polloi saddled up to an expansive carved mahogany bar to sample the latest mixed drinks (like the Manhattan, invented here) served in fine crystal and accompanied by a white linen napkin to wipe one’s mustache.

The Hoffmann House’s “Nymphs and Satyr” by William-Adolphe Bouguereau, 1873. (Clark Art Institute)

If you could afford it, you could catch a breeze while sipping champagne at one of New York’s many elaborate roof gardens. The Hotel Astor, United States Hotel and Hoffmann House all had beauties, but the most opulent by far was atop the Waldorf Astoria. After displaying your lavish garb to gawkers along the hotel’s Peacock Alley, you would be elevated to a rooftop wonderland, stretching across 7 city lots, brimming with fountains, trees, waterfalls, fish ponds, and an annual florist bill of $50,000.

Atop the Waldorf Astoria.

Enough. Let’s go slumming.

Meanwhile, downtown things were quite different. Water Street was a thoroughfare of vice and iniquity, every tenement filled with dance halls, brothels and saloons, all fueled by the cheapest liquor. Its criminals were as vicious as any in the city’s history, thanks to the handy nearby graveyard known as the East River. At the Hole-in-the-Wall you might run into Gallus Mag, a.k.a. “the most savage living female.” She would drag a male victim into an alley by clutching his ear in her teeth, and then biting it off, adding it to her jar of ears behind the bar. If biting’s your thing, at Kit Burns’ Sportsman Hall you could watch Jack the Rat bite the head off a mouse for a dime. Rats cost a quarter.

If one were seeking carnal entertainment, the crowded concert saloons were the ticket. Here you’d find the so-called “Pretty Waiter Girls” who wore bells on their red kid boots, and were available for dancing, both vertically and horizontally. You might also meet “Dolly Mops” or “Sailor’s Tarts” who slinked their rackets along the waterfront. John Allen’s Saloon had upper chambers available for quick tricks, but since John was a religious sort, each room included a bedside bible.

Just north, the Bowery had been known around the world as an entertainment mecca, but in the late 19th century morphed into a place of drunken homelessness. As the theater district moved north, pawn shops, brothels and flophouses moved in. Although Harry Hill’s joint served cops, judges, lawyers and bankers gone “slumming,” Billy McGlory’s attracted hardened criminals, known to slip unsuspecting victims knock-out drops, leaving them to wake up in an alley without clothes or money. Billy’s also featured prostitutes with bells on their red kid boots, but they were boys.

Harry Hills’

Further north lay the Tenderloin, a brash newer area of vice on 6th Avenue between 14th to 48th Streets, which hit its stride in the 1890s. It got its name from policeman Clubber Williams, who, when transfered here from a quieter beat, exclaimed “I used to have chuck steak, now I got tenderloin!” Due to exorbitant pay-offs to Tammany Hall, the saloons and brothels here enjoyed a much more refined clientele then the downtown slums. The French Madame’s was the most respectable “house” in the city, and the Haymarket dance hall achieved worldwide notoriety for its notoriousness.

“The Haymarket” by John Sloan, 1907. (Brooklyn Museum)

Ready to dry out?

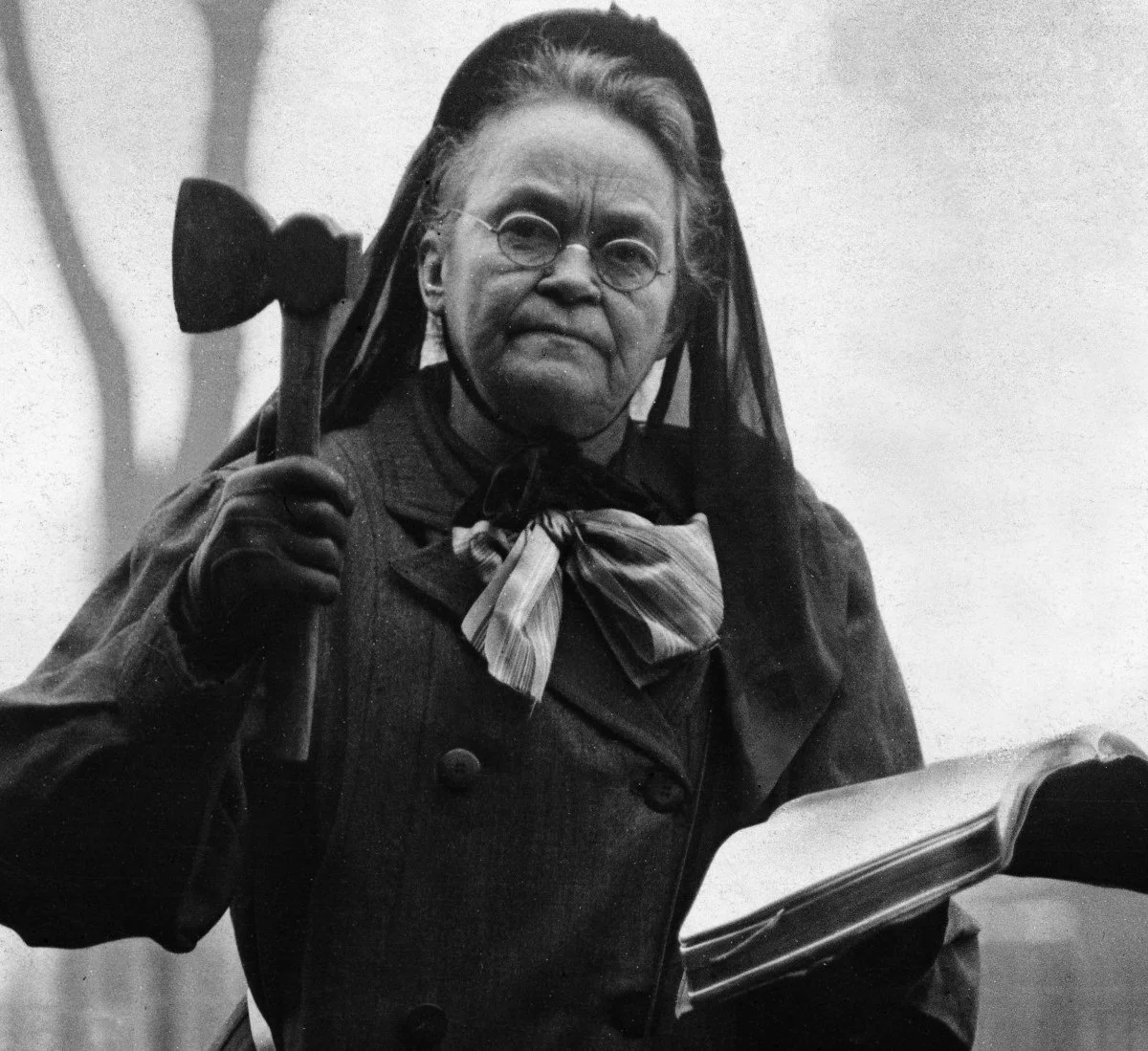

By the time the 20th century rolled around, the temperance movement, led mostly by women, had been in full swing for 50 years. They had a point: bars did not allow women, who had to suffer at home with the kids while hubby was out drinking, gambling and philandering. The protest against alcohol and its effects was led by the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and one Carry Nation, “the Kansas Smasher,” who hatcheted her way through New York’s Tenderloin, busting up several saloons before being arrested. Congress succumbed to the pressure and finally passed the Volstead Act, or the 21st Ammendment, over President Wilson’s veto. Liquor was banned across the country beginning January 6, 1920, at 12:01am. Many Gotham taverns staged mock funerals, featuring coffins filled with booze bottles, and then closed their doors forever.

The Kansas Smasher

But the very next day the 50-50 Club opened over a garage on West 50th Street, launched by 50 members who paid a hundred bucks each to stash their hooch. The age of the speakeasy had begun. “Speaks” popped up everywhere, behind florist shops, through telephone booths and under pickle purveyors. They really did have peepholes in the entrances, and you had to know the password to get in. At Jack and Charlie’s (later the 21 Club), most of the booze was stored at the address next door, accessed via a massive cellar door (still there.) Up at the bar, there was an emergency button in case of a raid; it upended the liquor shelves and sent the contents hurtling down a shaft into the sewer.

The 21 Club’s basement stash, now its wine cellar.

While keeping one eye out for the law, speaks competed with each other for customers, offering a startling array of entertainment with tiny tables, dance bands and floor shows, as immortalized by Hollywood. After an insulting mistress of ceremonies, like Texas Guinan, welcomed you with a hardy “hello, sucker!” you could enjoy Jimmy Durante, Ruby Keeler or Fred & Adele Astaire. Mingling with mobsters, bootleggers and flappers were all part of the thrill. Later at night throngs would journey up to Harlem, where the “Jazz Age” was launched, to catch Duke Ellington’s orchestra at the Cotton Club, Fletcher Henderson at Connie’s Inn, or dance till dawn at Small’s Paradise or the Savoy Ballroom. No other town personified the Roaring Twenties as vividly as New York.

“Hello, sucker!” - Texas Guinan

The federal government had alloted only $4.7 million for nation-wide enforcement of Prohibition; New York City hosted only 129 federal agents. And as far as the local cops were concerned, they were eager to take bribes along with their drinks. With over 30,000 speakeasies operating in the city (32 alone on one block of West 52nd Street), no one could stop the fun-seeking lawbreakers, and few had the incentive to do so. By the end of Prohibition in 1933, the number of places selling alcohol in the city had doubled.

Flappers (as if you didn’t know.)

Since women were welcomed into speakeasies with open arms, many didn’t want Prohibition anymore. “The Women’s Organization for National Prohibition Reform,” was established, which grew to 1.1 million members and helped to end the “Noble Experiment” which their teetotaling sisters fought to establish.

Café Society

Many of the speakeasies of the 1920s became the swanky nightclubs of the 40s and 50s. Jack and Charlie’s 21 Club was a survivor until recently, occupying the entire building and attracting the city’s most notable literati past its jockey hitching posts. The hidden booze vault became their wine cellar. Also located on “Swing Street” was Leon & Eddie’s, which welcomed the theatre crowd. Sherman Billingsly’s Stork Club boasted a stunning black-and-white interior, a solid gold entrance chain and iconic ashtrays, and John Perona’s zebra-striped El Morocco had a dance floor so huge that its far side was known as “Siberia.” And then there is the magnificent revolving Rainbow Room atop 30 Rock, an Art Deco masterpiece (still in business) which single-handedly made New York City “the most glamorous place on Earth,” and where a new cocktail was introduced called the Cosmopolitan.

The incomparable Rainbow Room. (Rockefeller Center Archives)

The 60s, 70s and 80s gave birth to the three-martini lunch, the polynesian mai tai dinner, and shots of that latest rage, tequila. English and Irish pubs proliferated, and jazz found a new home in the Village.

The first integrated nightclub, Café Society, in Greenwich Village. (LIFE Magazine, Time Inc.)

Singled out

An interesting scene developed in the 1970’s which could only have happened in New York. 800,000 young single women lived on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, mostly secretaries and “stewardesses.” Women weren’t welcome at the city’s sawdust saloons and lobby bars, so there were few places for them to congregate with men. Then a young perfume salesman named Alan Stillman bought one of those men-only saloons on East 63rd Street and planned to open a pleasant, upbeat watering hole wherein young singles could co-mingle happily. He called it T.G.I. Fridays. New York (and America) would never be the same again, sort of.

The original T.G.I. Fridays on East 63rd and First. (Photo by Ralph Morse, The LIFE Picture Collection, Getty)

Stillman had no experience in hospitality or interior design. He decorated the world’s first singles bar with fake Tiffany lamps and ferns (also giving birth to the “fern bar”) and dressed his bartenders in red-and-white striped soccer shirts. “If you think that I knew what I was doing, you are dead wrong,” he confessed to The New Yorker. But he must have done something right. Immediately Stillman had to hire a doorman to control the crowds of young folks, especially women, waiting to get into Friday’s (the simultaneous introduction of the birth control pill aided attendance.) Soon many other ferny singles bars opened throughout the neighborhood, including the popular Maxwell’s Plum across the street. Stillman eventually sold Fridays; it morphed into today’s family-friendly suburban chain famous for loaded potato skins, with 1,000 locations nationwide.

NYCocktails

Important cocktail history took place in New York, where the most famous and inventive bartenders held court at the most influential watering holes. The Golden Age of mixed drinks lasted from the post-Civil War era through WWI. This is when the first cocktail guides were published, like 1876’s How To Mix Drinks by Jerry Thomas (see bio.) Every bartender worth his salt needed to know how to prepare hundreds of obscure concoctions, from the Gin Daisy to the Salty Dog to the Depth Charge, and remember each customer’s preferences. And the truly gifted ones invented many classic (and some bizarre) cocktails themselves.

The world’s first cocktail guide, by the amazing Jerry Thomas.

Prohibition put an end to the cocktail. It’s difficult to disguise the taste of bathtub gin, moonshine or rotgut whiskey no matter what you mix with them. Taste was no longer a priority. By the time Prohibition, the Great Depression, and World War II were over, the going drinks were boring scotch on the rocks or the ubiquitous gin martini. It seems the taste for (and the competance to make) creative, flavorsome mixed drinks was gone forever. But not so. Today’s mixologists are at it once again, exploring past preparations and inventing new ones with a myriad of craft cocktails, available at an upscale bar near you.

Let’s sip some classic New York City cocktails.

The Manhattan, the quintessential New York cocktail, was invented in the Manhattan Club in the 1870s, and appeared in How To Mix Drinks in 1876. A mixture of rye or bourbon, bitters, vermouth and a stemmed cherry, it can be made sweet, semi-dry or dry, depending on the type of vermouth.

There is, of course, the Bronx Cocktail as well. It was first made by Johnnie Solon at the Waldorf Astoria, after he had visited the Bronx Zoo. It contains gin, both sweet and dry vermouths, and orange juice.

Sure enough, there’s the Brooklyn Cocktail, created by Maurice Hegeman in 1910 at Schmidt’s Cafe, near the Brooklyn Bridge. Originally made with absinthe, hard cider and ginger ale, today it’s rye, dry vermouth, bitters, and maraschino cherry liqueur. (Yes, there is a Queens Cocktail and a Staten Island Cocktail as well. And don’t forget Long Island Iced Tea.)

Today the most popular NYC-born cocktail in America is the Cosmopolitan, devised by bartender Dale Degraff at the Rainbow Room in the early 1980s. It was popularized by the Odeon in Tribeca, and then took over the country after being featured on Sex and the City. Today’s recipe calls for citron vodka, cranberry juice, lime juice, orange liqueur, and an orange peel.

The Martini has no definitive origin story. Some sources cite Jerry Thomas (see bio). It was served in New York from the late 1800s onwards. For a century it was made with gin and vermouth, but the latest generation prefers vodka (as in most all of their drinks; gin has divebombed in popularity.)

Three popular cocktails were born at the old Waldorf Astoria: the Old Fashioned, made with muddled sugar, soda and whiskey, the Rob Roy, similar to a Manhattan, made with scotch rather than whiskey, and the Gibson, really a gin martini served with pearl onions instead of olives.

The Bloody Mary may have had its start in the Manhattan Club as a “tomato cocktail.” When bartender Pete Petiot introduced it at the St. Regis Hotel’s splendid King Cole Bar, it was called a Red Snapper, and later a Bloody Mary. Today it’s made with vodka, tomato juice, worcestershire sauce, hot sauce and celery salt (and, if you’re in a New York bar, they’ll add horseradish.)

Let’s drink to surviving historic taverns.

Fraunces Tavern, the oldest pub in the city, is perfectly preserved. It has a serviceable bar on the ground floor and Washingtonian memorabilia upstairs. 54 Pearl Street.

White Horse Tavern, the city’s second-oldest bar, opened in 1880. Famous literary patrons include Dylan Thomas, Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac. 567 Hudson Street.

McSorley’s Old Ale House is the real deal of Irish brew joints since 1854. It can get rowdy (that’s the point.) Choose light or dark ale, and saltines, cheese and onions. 15 East 7th Street.

Landmark Tavern was opened in 1868, when the area was called Hell’s Kitchen. The gangs and gangsters are gone, but the place looks like they’re still around. 626 11th Avenue.

Old Town Bar, 1892, lives up to its name, with its wood panelling, tiled floors, and the celebated urinals in the men’s room (guys: you’ll see why.) 45 East 18th Street.

Pete’s Tavern from 1864 is another writer’s den, most notably neighbor O. Henry, who penned Gift of the Magi here. The 40-foot rosewood bar and tin ceiling are originals. 129 East 18th Street.

The Stonewall Inn, although of more recent vintage, is no less historic. The legendary Uprising of the LGBTQ+ community took place here in 1969; it’s been named a National Historic Landmark. 53 Christopher Street.

The Ear Inn, a 210-year-old Soho outpost, was established by an African Amercan, James Brown. The unassuming barroom has survived as is since 1817. The neon “B” was taped to become an “E” in 1977, to promote Ear Music Magazine, published in the building. 326 Spring Street.

So that’s our pub crawl through New York’s drinking history. If you’d like another round, you’re in luck…